Reimagining pedestrian cut throughs and pedestrian streets

Thu, July 8, 2021 | Urban Design | Walking and CyclingThis post from Malcolm McCracken, a Transport Planner at MRCagney, was originally posted on LinkedIn.

If you know your neighbourhood like the back of your hand, you know where the pedestrian cut throughs are. You also know which ones feel scary, and which ones you would avoid. Why is this? If a cut through is put in place to improve access, shouldn’t it be inviting, safe, and functional? As our cities change, we have an opportunity to improve the humble cut through, fundamentally changing the role that space plays.

In my last article, I discussed the need for improving walkability to rapid transit and breaking up large street blocks to create a more permeable walking network. I’m planning to publish further posts on ‘how we do this’ but first I thought it would be important to share what the vision for this new walking network looks like.

I envision a city connected by a fine grained network of pedestrian streets, making it easy to walk for local journeys and to public transport, creating new safe public spaces for neighbours to meet and children to play, supporting a liveable city as population density increases. To achieve this vision, we need to be improving existing cut throughs as well as adding new pedestrian connections.

So what is the problem with existing pedestrian links?

When thinking about pedestrian links or cut throughs, it is easy to jump to the poorly designed and narrow pedestrian cut throughs at the end of cul-de-sacs developed in the 20th Century. These have several issues which prevent them encouraging walking and often cause more issues than they solve.

These include:

- High fences or hedges between the path and neighbouring properties are common and create safety issues by removing passive surveillance.

- Barriers like staples, designed to stop vehicles and bikes from using the route, create barriers for people using mobility aids and prams.

- Lighting, when it does exist, is often not maintained, either with lightbulbs failing over time or trees growing up around lights, reducing their effectiveness.

- The worst cut throughs have a dog leg in the middle, meaning people cannot see who may be walking towards them, increasing perceived and real safety issues.

A not uncommon type of cut-through in Auckland with a large bend in the path meaning a user cannot see who may be ahead of them - Auckland Council Geomaps

In short, many cut throughs as we commonly know them are unsafe. They are definitely not public spaces that communities take pride in, and they don’t serve any additional function. The general safety issues and unpleasantness to use can be a disincentive considering walking a local trip, including walking to rapid transit.

A typical cut-through in Tāmaki Makaurau-Auckland, not looking particularly safe or inviting - Source: Google Streetview

Instead of intimidating and unwelcoming places like the cut throughs described above, cities should provide pleasant and safe walking routes that encourage people to walk for local journeys, including to access public transport.

What are the key features to developing pleasant and safe walking routes?

Passive surveillance - from neighbouring properties and the streets which the cut through joins.

Width - Pedestrian links need to be wide enough for two people with prams, wheelchairs, or mobility aids to comfortably pass each other without having to brush the fence or hedge. This width should be at least 4 to 5 metres.

Lighting – placed at regular intervals and at lower heights to ensure there is no obstruction from neighbouring trees, that it directly lights the path and limits the amount of light spilling into neighbouring properties.

How to improve existing links

Where existing cut throughs exist, we need policies to widen them as the neighbouring properties are developed. These policies should also require new units to front the cut throughs, to improve passive surveillance. An example of this is a recently re-opened pedestrian link in Kāinga Ora’s Roskill South neighbourhood between Freeland Ave and Dominion Rd. The cut through width is more than double the original 2.5 metres, the path itself is also wider, it has new lighting and some of the neighbouring units overlook the path.

The pedestrian link between Freeland Ave and Dominion Rd has been widened as Kāinga Ora developed on either side of the link

Of course, widening that link was also easier to achieve in a government-led development where the majority of houses and streets were being redeveloped. We could invest in widening pedestrian links by simply buying land from neighbouring properties but this would be complex, expensive and time consuming. Particularly to implement at a neighbourhood or rapid transit catchment scale, to deliver network benefits.

Instead, what policies could we implement to improve pedestrian cut throughs by leveraging from private development? Furthermore, how can we develop new pedestrian links to break up large street blocks to improve walkability? And to ensure this is successful, what incentives and benefits are there for the developer and future residents to make?

Pedestrian Streets

To achieve all of the above, we must reimagine current pedestrian cut throughs as pedestrian streets.

Despite this name, the idea behind these streets is not to ban bikes and micro mobility, but to create spaces that are designed to prioritise slower movement, access to properties, and social neighbourhood activities and interactions.

The key action to this, is requiring units to face the pedestrian space. Instead of dark lanes with little passive surveillance, the space that was previously a “cut through” becomes a street and the primary entry point to the properties. This makes the space a point guests arrive through, and a place neighbours can regularly bump into each other and engage in conversation on neutral ground, while also providing a safe space for children to play. The space has multiple purposes, increasing the general foot traffic which increases the feeling of safety. Furthermore, it can support residents in operating small businesses, by allowing ground floor spaces to become the front door to a home office, small cafes or speciality bakery, acupuncture or physiotherapy studio etc.

A good example of units facing a pedestrian street in Aotearoa, sits in a recent development on Lichfield Street in Christchurch’s East Frame development. A row of townhouses front either side of a 5-metre-wide street, with small trees and low-level planting on each edge and between each unit. It adds a new pedestrian connection through a 130x50m street block, which while not particularly big anyway, still adds a new more direct and pleasant walking route. However, it is worth noting that this was created in a large-scale redevelopment area, so would undoubtedly be simpler to implement than it would be to retrofit in most suburban contexts.

A new pedestrian street in Christchurch's East Frame

The opportunity - Creating new pedestrian streets through private development

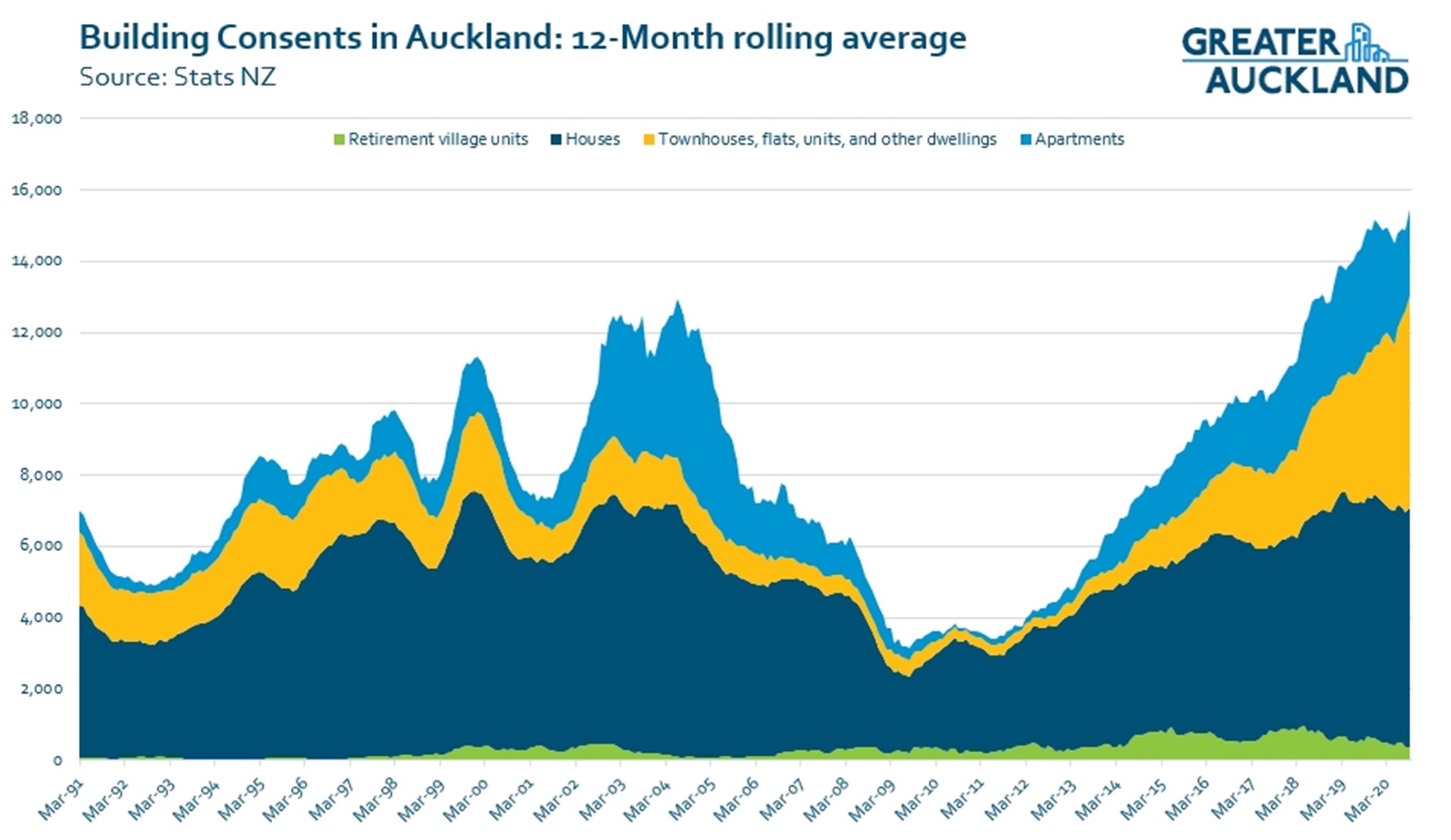

The up zoning of much of Tāmaki Makaurau through Unitary Plan has led to the biggest residential construction boom since the 1970s. The most significant growth is in Townhouses and Apartments, particularly in existing urban areas. Auckland has a lot of long skinny sites which mean it is difficult to avoid creating ‘rear units’ which don’t face the front of the site but sit perpendicular, particularly with townhouse developments. These developments are often described as ‘sausage flats’ with negative connotation. Creating pedestrian streets can mean these rear units can instead have a front door to a pedestrian only street creating a better urban design outcome and improving the walking network.

Source: https://www.greaterauckland.org.nz/2020/11/10/building-consent-surge/

To create pedestrian streets in an existing residential area, can be done through two methods. Firstly, upgrading existing pedestrian cut throughs and secondly, creating new streets on pedestrian desire lines to break up large street blocks and make walking journeys more direct.

Upgrading existing pedestrian links to pedestrian streets

One option to achieve this, a new overlay could be created within the Unitary Plan, applying to all property which borders an existing cut through. This overlay would require redevelopment of the site to:

- Be set back from the boundary with the cut through to allow a widened connection to be built.

- For rear units not fronting the main street to:

- Front the pedestrian street.

- Have access to and from the pedestrian street.

In this approach, widening the corridor requires land being transferred from the private property to council. This would be a disincentive for developers to develop those sites where this overlay applies.

- Reduced development contributions as the developer is delivering new public spaces and connections.

- Increased development potential through one of:

- Increased height limit

- Reduction or removal of set-back from boundary with the pedestrian street and/or the main street

Redevelopment occurring without this policy in place, will likely lead to worse outcomes as well with taller developments reducing light to the existing cut throughs and making them feel more enclosed.

Creating new pedestrian streets

Where new development is occurring, we need policies and incentives through the planning system that support development to create new pedestrian streets to break up street blocks.

What if this development was mirrored on the neighbouring sites to create a comfortable pedestrian link through the street block

It is rare for a development to extend the width of a street block meaning for a new pedestrian street to be developed, it will likely have to occur through multiple developments over time. Developments could build access to rear units, via a pedestrian lane which is future proofed to be joined both through the street block as the property behind is developed and widened as the property to the other side is developed. Thus, creating a pedestrian street. For apartment developments there could be pedestrian access, small retail/commercial units or bike parking access provided from the side of the building. As the neighbouring property is developed, it can become a flourishing street with activities on both sides.

Neighbourhood Plans

This approach would likely require a higher-level evaluation of a neighbourhood’s street network, to identify where new connections are required most. The link could then be formally identified through a precinct or neighbourhood plan, effectively designating where connections would be added through development.

A risk with this process is it would make sites with identified pedestrian links less attractive for developers to build on, as some of the land would be given over to create the new link. Similar incentives to what are mentioned above for widening existing cut throughs may help compensate for the increased cost on the developer.

This plan could be developed in partnership with the local community to identify opportunities for increased density, new green spaces and zoning changes to encourage a range of activities in the neighbourhood, not just residential. A great starting point would be undertaken this assessment and introducing neighbourhood plans in the walking catchments of rapid transit stations that are being up zoned in response to the National Policy Statement on Urban Development.

Conclusion

Tāmaki Makaurau is going through significant change with redevelopment occurring across the city. Up zoning from the NPS-UD will likely accelerate this change. Creating pedestrian streets through redevelopment can help us create a vibrant, low carbon city.